Preface #

In the blog post “Langevin Dynamics”, we mentioned the concept of the “Boltzmann Distribution ”, which plays an important role in Energy-Based Models. At that time, since our focus was on langevin dynamics and its application in the machine learning community, we only presented the distribution expression (Equation (6) in this blog ) without a detailed derivation or explanation. Fortunately, I have been studying thermodynamics recently and am currently working with my advisor on writing a handbook that explores solid mechanics from a thermodynamic perspective. Through this process, I have gained a better understanding of the Boltzmann distribution and, more importantly, how the expression for entropy in statistical mechanics is derived. I figured this would be a great opportunity to fill in the gaps in my previous understanding of the related concepts.

Motivation Behind the Statistical Entropy #

Rudolf Clausius (1822-1888) introduced the concept of entropy

in 1865, which is macroscopically defined to measure the degree of disorder or randomness in a thermodynamic system. Many irreversible processes observed in nature are accompanied by an increase in the system’s entropy, i.e., $\mathrm{d}_\mathrm{i}S\geq 0$. However, from a microscopic perspective, these irreversible processes are essentially the result of atomic and molecular motion governed by fundamental physics, such as classical mechanics and quantum mechanics, which themselves are time-symmetric and do not exhibit irreversibility. This raises a series of intriguing questions:

- How can irreversible macroscopic processes emerge from the reversible motion of atoms and molecules?

- And what is the relation between a system’s entropy and its microscopic constituent particles?

Statistical Mechanics was then developed by Ludwig Boltzmann (1844-1906) to answer these queations.

The Number of Microstates #

The possible energy distribution of microscopic particles in a system is known as energy levels

, which are discrete rather than continuous. Let us now define the basic parameters of the isolated system under investigation: the system contains a fixed number of particles $N$, with a volume $V$ and a total energy $U$. The energy of each energy level is denoted as $\varepsilon_1,\varepsilon_2,\cdots,\varepsilon_l,\cdots$, represented as $\left\{\varepsilon_l\right\},\ l=1,2,\cdots$. The degeneracy

of each energy level (i.e., the number of measurable quantum states corresponding to each energy level) is $g_1,g_2,\cdots,g_l,\cdots$, represented as $\left\{g_l\right\}$. The number of particles occupying each energy level is $a_1,a_2,\cdots,a_l,\cdots$, denoted as $\left\{a_l\right\}$.

In a system composed of particles that are nearly independent, the interaction between microscopic particles is weak and can be neglected. Therefore, the internal energy of the system is simply the sum of the individual particle energies $\varepsilon_l$. Based on the constraints imposed by the particle number and system energy, we have

$$N=\sum_la_l;\quad U=\sum_la_l\varepsilon_l. \tag{1} \label{eq1}$$

Boltzmann proposed two important hypotheses for the equilibrium state of a system: the equiprobability principle and the most probable hypothesis.

The equiprobability principle states that, in thermodynamic equilibrium, all possible microscopic states of an isolated system within the same energy range are equally probable. Therefore, the probability that the particles of a system are in a particular distribution $\left\{a_l\right\}$ is actually proportional to the number of microstates satisfying that distribution. That is, $P\left(\left\{a_l\right\}\right)\propto W\left(\left\{a_l\right\}\right)$, where $W$ represents the number of possible microstates that correspond to distribution $\left\{a_l\right\}$.

The most probable hypothesis further states that, when a system reaches thermodynamic equilibrium, the distribution of its microstates will be the most probable, i.e., it corresponds to the distribution with the highest probability. Since the equiprobability principle ensures that all microstates are equally likely, the equilibrium state corresponds to the distribution that maximizes the number of microstates $W$. Therefore, our focus shifts to determining the most likely number of particles at each energy level, i.e., the most probable distribution (MPD) $\left\{a_l\right\}$.

The distribution of particles across different energy levels is clearly a combinatorial problem, where we need to distribute $N$ particles according to the numbers $a_1,a_2,\cdots$. Moreover, considering the degeneracy of the energy levels, a single particle at energy level $\varepsilon_l$ can actually occupy $g_l$ different quantum states. Thus, all the particles at this energy level can be arranged in $g_l^{a_l}$ ways, which further increases the value of $W$. In this way, the total number of possible microstates of the system can be expressed as

$$W=C_N^{a_1}C_{N-a_1}^{a_2}\cdots\prod_l g_l^{a_l}=\frac{N!}{\prod_l a_l!}\prod_l g_l^{a_l}. \tag{2} \label{eq2}$$

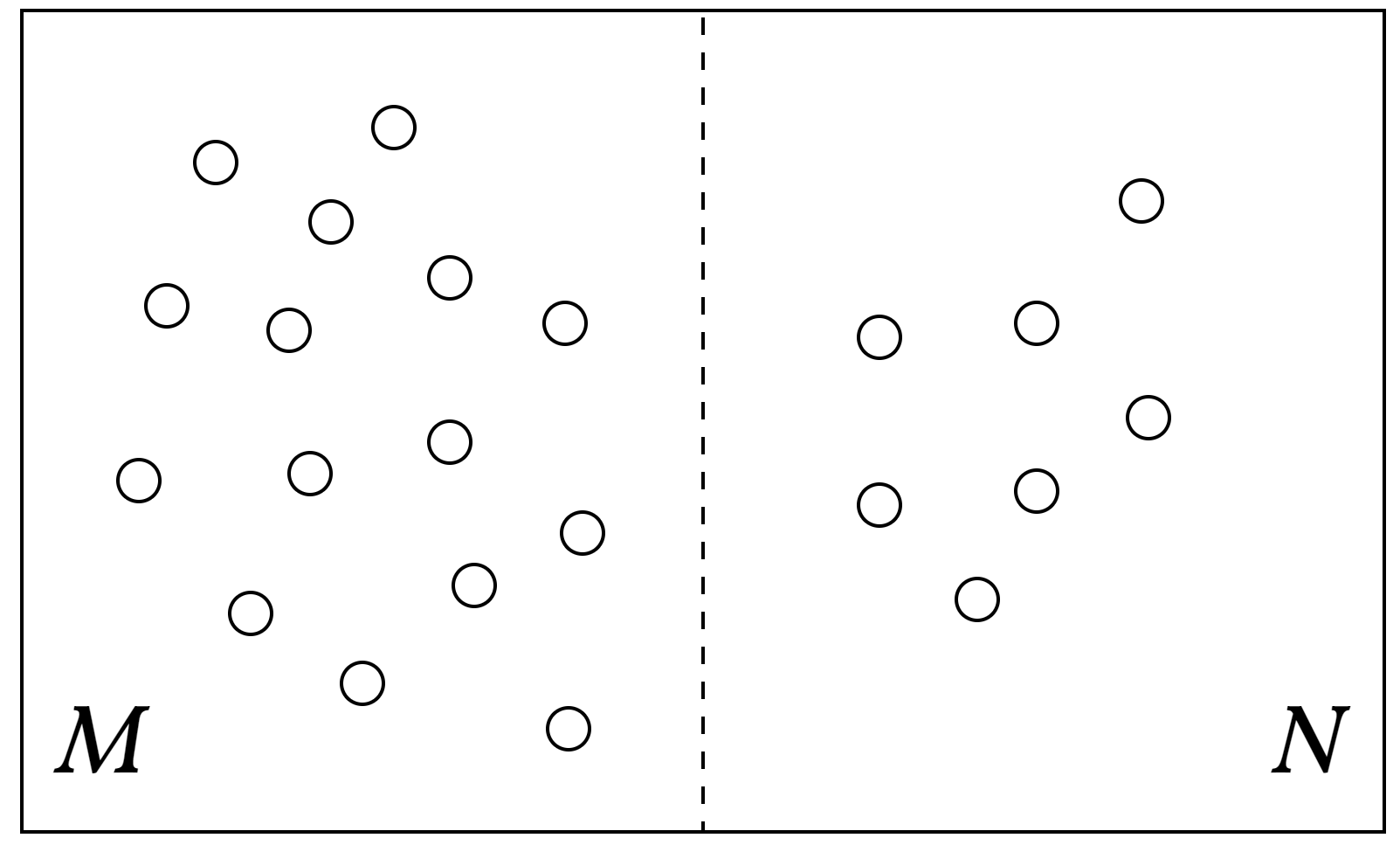

Now, I want to discuss Equation $\eqref{eq1}$ and the underlying concept with a simple example. Consider a box that is evenly divided into two sections, filled with gas. The left half contains $M$ gas molecules, while the right half contains $N$ gas molecules. Each molecule can be in either the left or the right part of the box. Here, we ignore the effect of degeneracy, i.e., $g_l=1,\text{ for }l=1,2,\cdots$, meaning the number of microstates $W$ is simply the number of ways to distribute $M+N$ gas molecules between the left and right halves of the box, as shown in Fig. 1, where we have $M$ molecules on the left and $N$ on the right

$$W=C_{M+N}^M=\frac{(M+N)!}{M!N!}, \tag{3} \label{eq3}$$

Figure 1: A combinatorial problem defined by distributing M+N gas molecules between the two halves of the box, with M molecules on the left and N on the right.

As mentioned earlier, the equilibrium state maximizes $W$. In this case, Equation $\eqref{eq3}$ reaches its maximum when $M=N$. This conclusion is intuitive: during the process of reaching equilibrium, the gas molecules gradually diffuse and spread uniformly to fill the entire space. When the system is in equilibrium, the left and right halves of the box must contain an equal number of gas molecules.

Derivation of the Boltzmann Distribution #

Referring back to the expression for the microstates number given by Equation $\eqref{eq2}$, we aim to determine the MPD of particles. At the thermodynamic equilibrium, $W$ is maximum, but the corresponding distribution $\left\{a_l\right\}$ should still satisfy Equation $\eqref{eq1}$. This forms a constrained optimization problem

\begin{align} \min_{\left\{a_l\right\}}\quad &-\ln W\left(\left\{a_l\right\}\right)\\ \mathrm{s.t.}\quad &\sum_l a_l-N=0\\ &\sum_l a_l\varepsilon_l-U=0, \tag{4} \label{eq4} \end{align}

where, for simplicity, we reformulate the problem of maximizing $W$ as an equivalent problem of minimizing its negative logarithm. Note that, the number of particles $N$ contained in real systems is sufficiently large, allowing us to further simplify the complex factorial operations using Stirling’s approximation:

$$\ln n!\approx n\left(\ln n-1\right),\quad n\gg 1, \tag{5} \label{eq5}$$

then, taking the logarithm of Equation $\eqref{eq2}$ and applying Stirling’s approximation, we obtain

$$\ln W\approx N\ln N-N-\sum_l\left(a_l\ln a_l-a_l\right)+\sum_la_l\ln g_l. \tag{6} \label{eq6}$$

For the constrained optimization problem given by the equality in Equation $\eqref{eq4}$, we first construct the Lagrangian function $\mathcal{L}$

$$\mathcal{L}=-\ln W\left(\left\{a_l\right\}\right)+\alpha\left(\sum_la_l-N\right)+\beta\left(\sum_la_l\varepsilon_l-U\right), \tag{7} \label{eq7}$$

here, the undetermined parameters $\alpha$ and $\beta$ are the Lagrange multipliers. According to the method of Lagrange multipliers

, for all energy levels $l=1,2,\cdots$, we have $\partial\mathcal{L}/\partial a_l=0$. This leads to the following result

$$a_l=g_l\cdot e^{-\alpha-\beta\varepsilon_l},\quad l=1,2,\cdots, \tag{8} \label{eq8}$$

this is called the Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution, which represents the most probable number of particles at energy level $l$, that is, the MPD of particles.

Based on the conservation of particle number in an isolated system, $\alpha$ can be further expressed in terms of $\beta$, allowing Equation $\eqref{eq8}$ to be rewritten as

$$a_l=N\frac{g_l\cdot e^{-\beta\varepsilon_l}}{Z},\quad Z=\sum_kg_k\cdot e^{-\beta\varepsilon_k}, \tag{9} \label{eq9}$$

where, $Z$ is called the partition function

, and $\alpha=\ln(Z/N)$. Dividing both sides of the above equation by $N$, we obtain the Boltzmann distribution we want

$$p_l=\frac{1}{Z}g_l\cdot e^{-\beta\varepsilon_l}. \tag{10} \label{eq10}$$

We have arrived at the very original form of the Boltzmann distribution, but still with a multiplier $\beta$ to be determined. Next, from the process of deriving the statistical entropy, we will determine the specific expression for $\beta$ (Equation $\eqref{eq16}$). And if we again ignore the effect of degeneracy, Equation $\eqref{eq10}$ will reduce to the distribution form in this previous blog

.

(Boltzmann) Statistical Entropy #

From the conservation of system energy, the internal energy $U$ can be related to the partition function $Z$ through

$$U=e^{-\alpha}\sum_lg_l\varepsilon_l\cdot e^{-\beta\varepsilon_l}=-\frac{N}{Z}\frac{\partial Z}{\partial\beta}=-N\frac{\partial\ln Z}{\partial\beta}, \tag{11} \label{eq11}$$

which is generally known as the statistical form of system’s internal energy.

Earlier, we derived the Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution for a system of distinguishable particles assuming it was isolated (Equation $\eqref{eq8}$). However, for a thermodynamic system that is not isolated, we need to take into account the effect of external parameters $\pmb{y}=(y_1,y_2,\cdots)$ (such as volume, magnetic and electric field, etc, which remain unchanged by the system’s internal state and are determined by external conditions). When these external parameters change, the surroundings do work on the system, increasing its internal energy $U$. If $\pmb{y}$ remains constant, we can treat the system as isolated again. Therefore, the energy of the particles can be expressed as a function of the external parameters, i.e., $\varepsilon_l=\varepsilon_l(\pmb{y})$. The change in energy level due to the varying external parameters is given by $\mathrm{d}\varepsilon_l=\frac{\partial\varepsilon_l}{\partial\pmb{y}}\cdot\mathrm{d}\pmb{y}$, where the partial derivative terms can be interpreted as the generalized force vector that exerted on a particle at energy level $\varepsilon_l$

$$\pmb{Y}_l=\frac{\partial\varepsilon_l}{\partial\pmb{y}}. \tag{12} \label{eq12}$$

The generalized force on the entire system is equal to the sum of the generalized forces acting on all particles

\begin{align} \pmb{Y}&=\sum_la_l\pmb{Y}_l=e^{-\alpha}\sum_l\frac{\partial\varepsilon_l}{\partial\pmb{y}}g_l\cdot e^{-\beta\varepsilon_l(\pmb{y})}\\ &=\frac{N}{Z}\left[-\frac{1}{\beta}\frac{\partial}{\partial\pmb{y}}\left(\underbrace{\sum_lg_l\cdot e^{-\beta\varepsilon_l}}_{\text{partition function}}\right)\right]=-\frac{N}{\beta}\frac{\partial\ln Z}{\partial\pmb{y}}, \tag{13} \label{eq13} \end{align}

note that, after the introduction of $\pmb{y}$, the partition function should also be the function of the multiplier $\beta$ and the external parameter $\pmb{y}$, i.e., $Z=Z(\beta,\pmb{y})$.

According to Clausius’s definition of entropy, $\mathrm{d}S=\delta Q/T$, where $\delta Q$ is the heat absorbed by the system, which is a path-dependent quantity, while entropy $S$ is a state function that is independent of the process. Therefore, $1/T$ serves as an integrating factor

for $\delta Q$, transforming it into the path-independent exact differential $\mathrm{d}S$. From the first law of thermodynamics, we have

$$\delta Q=\mathrm{d}U-\pmb{Y}\cdot\mathrm{d}\pmb{y}=-N\mathrm{d}\left(\frac{\partial\ln Z}{\partial\beta}\right)+\frac{N}{\beta}\frac{\partial\ln Z}{\partial\pmb{y}}\cdot\mathrm{d}\pmb{y}, \tag{14} \label{eq14}$$

multiplying Equation $\eqref{eq14}$ by the factor $\beta$, we obtain

\begin{align} \beta\delta Q &= -N\beta\mathrm{d}\left(\frac{\partial\ln Z}{\partial\beta}\right)+N\frac{\partial\ln Z}{\partial\pmb{y}}\cdot\mathrm{d}\pmb{y}\\ &= -N\beta\mathrm{d}\left(\frac{\partial\ln Z}{\partial\beta}\right)+N\left[\mathrm{d}\left(\ln Z\right)-\frac{\partial\ln Z}{\partial\beta}\mathrm{d}\beta\right]\\ &= N\mathrm{d}\left(\ln Z\right)-N\left[\beta\mathrm{d}\left(\frac{\partial\ln Z}{\partial\beta}\right)+\frac{\partial\ln Z}{\partial\beta}\mathrm{d}\beta\right]\\ &= N\mathrm{d}\left(\ln Z-\beta\frac{\partial\ln Z}{\partial\beta}\right). \tag{15} \label{eq15} \end{align}

From Equation $\eqref{eq15}$, we can find that $\beta$ is also an integrating factor for $\delta Q$. According to the theory of integrating factors, the ratio of any two integrating factors here remains a function of the system’s entropy $S$, that is

$$\beta=\frac{1}{k(S)T}. \tag{16} \label{eq16}$$

Consider an isolated system composed of two types of nearly independent particles, with energy levels given by $\left\{\varepsilon_l\right\}$ and $\left\{\varepsilon_l^\prime\right\}$, respectively. The distributions of the two types of particles are represented by $\left\{a_l\right\}$ and $\left\{a_l^\prime\right\}$. Also, the conservation of system’s particle and energy give

\begin{align} &\sum_la_l=N,\ \sum_la_l^\prime=N^\prime;\\ &\sum_la_l\varepsilon_l+\sum_la_l^\prime\varepsilon_l^\prime=U, \tag{17} \label{eq17} \end{align}

where, $N$ and $N^\prime$ are the number of particles in the two subsystems.

By introducing the three Lagrange multipliers $\alpha$, $\alpha^\prime$ and $\beta$ associated with the constraints in Equation $\eqref{eq17}$, and repeating the derivation as done for Equation $\eqref{eq8}$, we can show that both types of nearly independent particles follow the Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution. Moreover, due to energy conservation in the system, they share the same Lagrange multiplier $\beta$ for the energy constraint. When the two subsystems reach thermal equilibrium, they will have the same temperature $T$, which means that $k(S)$ in Equation $\eqref{eq16}$ must be a constant that is independent of the system’s entropy, known as the Boltzmann constant

$k_\mathrm{B}$. This is because entropy is an extensive variable, while temperature is an intensive one. Since the sizes of two subsystems weren’t specified in the derivation, if $k=k(S)$, the two systems in thermal equilibrium would not share the same Lagrange multiplier $\beta$.

Substituting Equations $\eqref{eq15}$ and $\eqref{eq16}$ into the definition of entropy, integrating, and choosing an appropriate constant of integration (to define the zero of entropy), we obtain

$$S=k_\mathrm{B}N\left(\ln Z-\beta\frac{\partial\ln Z}{\partial\beta}\right). \tag{18} \label{eq18}$$

At this point, we return to Equation $\eqref{eq5}$. When the system is in equilibrium, $a_l$ follows the Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution, with the corresponding Lagrange multipliers being expressed in terms of the partition function. In the end, we can connect the number of microstates $W$ with the partition function $Z$

$$\ln W\approx N\ln N+\alpha N+\beta U=N\left(\ln Z-\beta\frac{\partial\ln Z}{\partial\beta}\right), \tag{19} \label{eq19}$$

when the particles number $N$ is large enough (which is exactly the case in practice), we can replace the approximation with an equality without introducing perceptible error. By comparing Equation $\eqref{eq18}$ and Equation $\eqref{eq19}$, the (boltzmann) statistical entropy is finally obtained

$S=k_\mathrm{B}\ln W. \tag{20} \label{eq20}$

The value of $k_\mathrm{B}$ can be obtained from the free expansion of an ideal gas (satisfying the state equation $pV=nRT$), where the system is assumed to transition from state 1 to state 2. During this process, the entropy change of the ideal gas system is given by $\Delta S=\int_1^2\frac{\delta Q}{T}=nR\ln\frac{V_2}{V_1}$. In a system with $N$ particles occupying a volume $V$, each particle’s position can vary freely within the volume $V$. So, for $N$ particles, the total phase space volume for the degrees of freedom of position is roughly $V^N$. In simple terms, the number of microstates of the system is proportional to the phase space volume (a detailed proof is omitted here), i.e., $W\propto V^N$. Using the statistical entropy formula (Equation $\eqref{eq20}$), the entropy change for the free expansion of an ideal gas can be written as $\Delta S=k_\mathrm{B}\ln\frac{W_2}{W_1}=k_\mathrm{B}N\ln\frac{V_2}{V_1}$. Therefore, we get

$$k_\mathrm{B}=\frac{nR}{N}=\frac{R}{N_\mathrm{A}}\approx 1.381\times 10^{-23}\,\mathrm{J\cdot K^{-1}}, \tag{21} \label{eq21}$$

where, $R\approx 8.314\,\mathrm{J/(K\cdot mol)}$ is the gas constant

, and $N_\mathrm{A}\approx 6.022\times 10^{23}\,\mathrm{mol^{-1}}$ is called the Avogadro constant

.

Last modified on 2026-01-04