Preface #

The introduction of vector fields allows us to understand and mathematically model a vast array of phenomena where both magnitude and direction vary over space. It provides a way to capture the idea of a vector quantity (such as velocity, force, or magnetic field) at every point in a given space or region, which is essential in many areas of science and engineering generally described by partial differential equations (PDEs). Vector calculus studies the (partial) differentiation and (multiple) integration of vector fields. It features three key differential operators, i.e., grad, div and curl, and several related theorems and identities.

Therefore, mastering this knowledge proficiently helps us gain a deeper understanding of various complex physical phenomena and also allows us to apply these theorems and equations to draw interesting and meaningful conclusions in our own specific research fields. However, I found myself often confused by their definitions during my previous studies, without a unified perspective to think about the connections between them, which led to a shallow understanding of these concepts and a rather vague memory of them. So, in this blog, I hope to clarify the definitions of gradient, divergence, and curl, as well as the corresponding theorems, including Green’s Theorem, Gauss’s Theorem and Stokes’ Theorem. I hope this will contribute, even if only in a small way, to both my own understanding and that of the readers.

Gradient #

Coordinate-free Definition #

The gradient is a vector-valued function corresponding to a multivariable real-valued differentiable function $f: \mathbb{R}^n\to\mathbb{R}$, denoted $\nabla f$. And in the context of field theory, it can also be viewed as a differential operator that maps a scalar field into a vector field ($\nabla f: \mathbb{R}^n\to\mathbb{R}^n$).

The expression $\nabla f(p)\neq 0$ identifies a vector that points in the direction of the greatest rate of increase of $f$ at point $p$, with its magnitude indicating the rate of increase in that direction. In contrast, $\nabla f(p)=0$ actually indicates the existence of a stationary point. The “gradient” can be defined in a coordinate-free manner, that is,

$$\mathrm{d}f=\nabla f\cdot\mathrm{d}\pmb{x}, \tag{1} \label{eq1}$$

where $\mathrm{d}f$ is the total infinitesimal change in $f$ resulting from an infinitesimal displacement $\mathrm{d}\pmb{x}$. $\nabla f$ is defined as the gradient of $f$, and is also commonly denoted as $\mathrm{grad} f$. It can be seen that the change in $f$ is maximized when the infinitesimal displacement is aligned with the direction of the gradient, which corresponds exactly to the physical interpretation of $\nabla f$ that we discussed earlier. Equation $\eqref{eq1}$ also shows the relation between the total differential of a function and its gradient.

The dot product of $\mathrm{grad}f$ with any vector $\pmb{l}$ at point $p$ is the directional derivative of that function along $\pmb{l}$

$$D_{\pmb{l}}f(p)=\nabla f(p)\cdot\pmb{l}.$$

Representation in Cartesian Coordinates #

When $f$ is represented in a coordinate system with an orthonormal basis, the corresponding gradient is given by an $n$-dimensional vector consisting of partial derivatives of $f$ at point $p=\left(x_1,x_2,\cdots,x_n\right)$ (if $f$ is differentiable at $p$), i.e.,

$$\nabla f(p)=\left[\frac{\partial f}{\partial x_1}(p),\cdots,\frac{\partial f}{\partial x_n}(p)\right]^\mathrm{T}, \tag{2} \label{eq2}$$

here, $\nabla=\left(\frac{\partial}{\partial x_1},\cdots,\frac{\partial}{\partial x_n}\right)$ is the nabla operator. Specifically, for three-dimensional Cartesian coordinate system (with $\pmb{i},\pmb{j},\pmb{k}$ being the standard unit vectors along $x,y\text{ and }z$ coordinates), the gradient takes the form

$$\nabla f=\frac{\partial f}{\partial x}\pmb{i}+\frac{\partial f}{\partial y}\pmb{j}+\frac{\partial f}{\partial z}\pmb{k}.$$

Generalization #

For a differentiable vector-valued function $\pmb{f}: \mathbb{R}^n\to\mathbb{R}^m$, the gradient of $\pmb{f}$ is a matrix of size $m\times n$, known as the Jacobian matrix

$$\nabla\pmb{f}\triangleq\pmb{J}=\left[\frac{\partial\pmb{f}}{\partial x_1},\cdots,\frac{\partial\pmb{f}}{\partial x_n}\right]=\frac{\partial f_i}{\partial x_j}\left(\pmb{e}_i\otimes\pmb{e}_j\right),$$

where $\otimes$ denotes the tensor product

operation, $i=1,\cdots,m;\ j=1,\cdots,n$. $\pmb{e}_i$ are orthonormal basis vectors.

Gradient plays a fundamental role in a wide range of scientific fields, from helping optimize machine learning models (such as the classic gradient descent and automatic differentiation algorithms) to modeling physical systems and designing engineering solutions.

Divergence #

Coordinate-free Definition #

The divergence is a differential operator that maps a vector field $\pmb{F}$ to a scalar one. In physics, it represents the “sourceness” or “sinkness” of a field and is always associated with the concept of flux, denoted $\nabla\cdot\pmb{F}$ or $\mathrm{div}\pmb{F}$.

The expression $\left.\nabla\cdot\pmb{F}\right|_p\geq 0$ indicates that there is a source at point $p$, meaning the field is “spreading out” from that location. Conversely, $\left.\nabla\cdot\pmb{F}\right|_p\leq 0$ suggests a sink, where the field is “converging” or “flowing into” the point. $\left.\nabla\cdot\pmb{F}\right|_p=0$ means the vector field is neither expanding nor contracting at that point, which is often interpreted as the field being conservative or incompressible.

The coordinate-free definition of “divergence” is generally stated as the volume density of the outward flux of a vector field from a closed infinitesimal volume $V$ around a given point $\pmb{x}_0$. Mathematically, this is given by

$$\left.\nabla\cdot\pmb{F}\right|_{\pmb{x}_0}=\lim_{V\to 0}\frac{1}{|V|}\subset\kern{-3pt}\supset\kern{-16.5pt}\iint_{S(V)}\pmb{F}\cdot\pmb{n}\,\mathrm{d}S, \tag{3} \label{eq3}$$

where $|V|$ and $S(V)$ are the volume and closed surface of $V$, respectively. $\pmb{n}$ denotes the outward unit normal to that surface.

Representation in Cartesian Coordinates #

The above definition (Equation $\eqref{eq3}$) is rarely used for directly calculating the divergence due to its lack of intuitiveness. Actually the definition of divergence can be simplified reasonably when working with Cartesian coordinates.

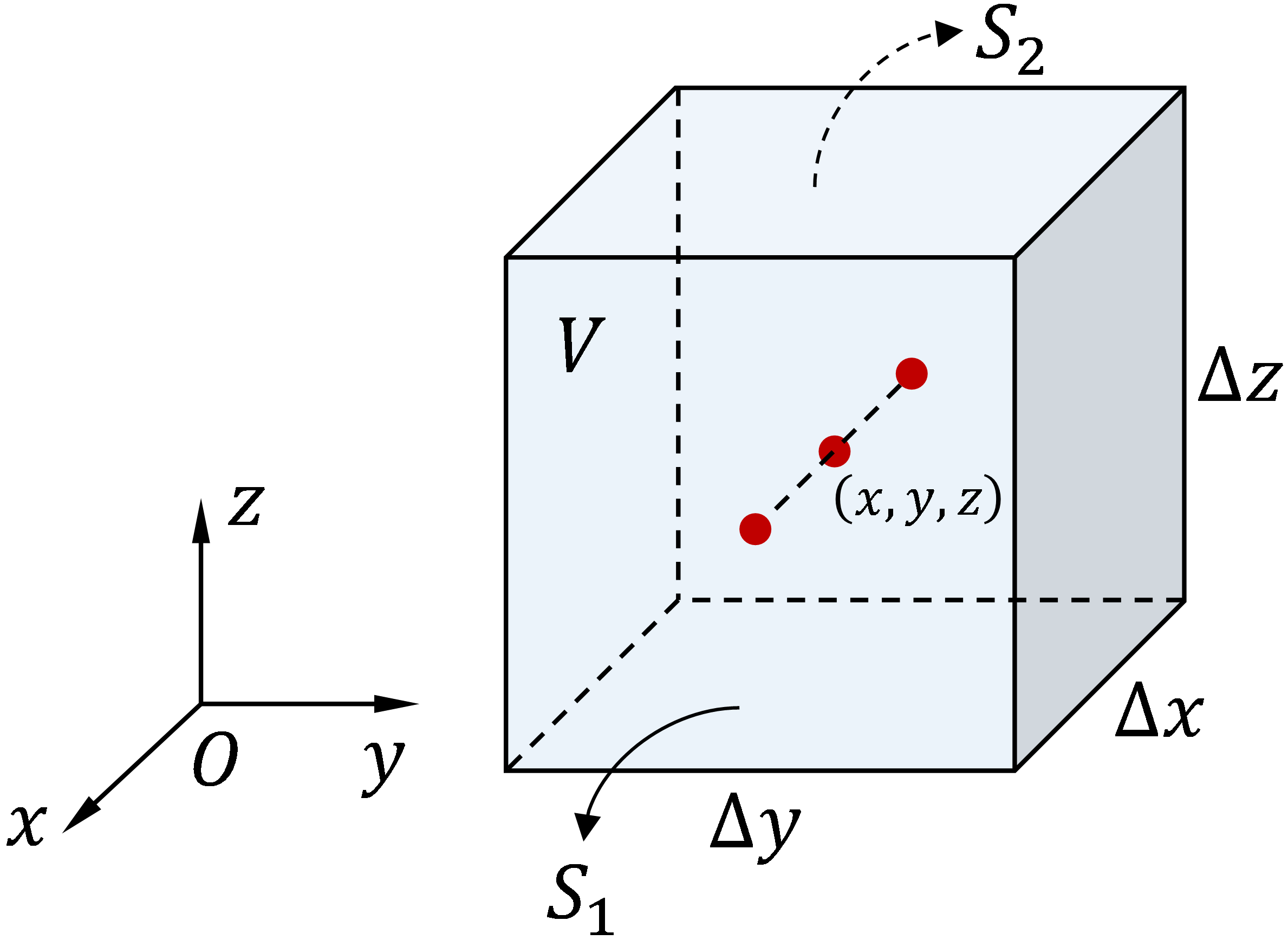

Figure 1: An infinitesimal rectangular parallelepiped centered at (x,y,z), with edges of length Δx, Δy and Δz.

Consider an infinitesimal rectangular parallelepiped centered at $(x,y,z)$, as shown in Fig. 1. We here first calculate the surface integral of an arbitrary vector-valued function $\pmb{F}(x,y,z)$ over two opposing surfaces, $S_1\text{ and }S_2$. When the volume shrinks to zero, the surface integral can be approximated as $\pmb{F}\cdot\pmb{n}$ at the center of that surface multiplied by the surface area. Therefore, we have

\begin{align} \iint_{S_1}\pmb{F}\cdot\pmb{n}\,\mathrm{d}S&=\iint_{S_1}F_x(x,y,z)\,\mathrm{d}S\approx F_x\left(x+\frac{\Delta x}{2},y,z\right)\Delta y\,\Delta z; \tag{4} \label{eq4}\\ \iint_{S_2}\pmb{F}\cdot\pmb{n}\,\mathrm{d}S&=-\iint_{S_2}F_x(x,y,z)\,\mathrm{d}S\approx -F_x\left(x-\frac{\Delta x}{2},y,z\right)\Delta y\,\Delta z. \tag{5} \label{eq5} \end{align}

With equations $\eqref{eq4}$ and $\eqref{eq5}$, the surface integral of $\pmb{F}$ on two opposing surfaces is given by

$$\lim_{V\to 0}\frac{1}{|V|}\iint_{S_1+S_2}\pmb{F}\cdot\pmb{n}\,\mathrm{d}S=\lim_{\Delta x\to 0}\frac{F_x\left(x+\frac{\Delta x}{2},y,z\right)-F_x\left(x-\frac{\Delta x}{2},y,z\right)}{\Delta x}=\frac{\partial F_x}{\partial x},$$

similarly, the other two groups of surface integrals are obtained. Finally, we arrive at the divergence of a continuously differentiable vector field $\pmb{F}$ under the Cartesian coordinates

$$\nabla\cdot\pmb{F}\triangleq \mathrm{div}\pmb{F}=\frac{\partial F_x}{\partial x}+\frac{\partial F_y}{\partial y}+\frac{\partial F_z}{\partial z}.$$

Gauss’s Theorem (Divergence Theorem) #

In this section, we present a famous theorem regarding the divergence, namely Gauss’s Theorem, which relates the flux of a vector field through a closed surface to the divergence of the field over the enclosed volume. Let $\pmb{F}$ be a continuously differentiable vector field defined on a neighborhood of a closed volume $V$, and let $S=\partial V$ be the (piecewise smooth) boundary of that region. The Gauss’s Theorem states that

$$\iiint_V\nabla\cdot\pmb{F}\,\mathrm{d}V=\subset\kern{-3pt}\supset\kern{-16.5pt}\iint_S\pmb{F}\cdot\pmb{n}\,\mathrm{d}S, \tag{6} \label{eq6}$$

here, $\mathrm{d}\pmb{S}$ can be adopted as a shorthand for $\pmb{n}\,\mathrm{d}S$. One can refer to this webpage

for informal derivations of Equation $\eqref{eq6}$.

In Cartesian coordinates, the vector-valued function can be expressed as $\pmb{F}=F_x\,\pmb{i}+F_y\,\pmb{j}+F_z\,\pmb{k}$. Therefore, equation $\eqref{eq6}$ reduces to the familiar form

$$\iiint_V\left(\frac{\partial F_x}{\partial x}+\frac{\partial F_y}{\partial y}+\frac{\partial F_z}{\partial z}\right)\,\mathrm{d}x\mathrm{d}y\mathrm{d}z=\subset\kern{-3pt}\supset\kern{-16.5pt}\iint_S F_x\,\mathrm{d}y\mathrm{d}z+F_y\,\mathrm{d}x\mathrm{d}z+F_z\,\mathrm{d}x\mathrm{d}y. \tag{7} \label{eq7}$$

Take fluid dynamics as an example, let’s consider a fluid flowing through a given volume. The divergence of the velocity field indicates whether the fluid is expanding or contracting at different points within the volume. The Gauss’s Theorem tells us that the total amount of fluid flowing out of the surface enclosing the volume is equal to the total rate at which the fluid is “created” or “lost” inside the volume.

Curl #

Coordinate-free Definition #

In vector calculus, the curl identifies a differential operator that maps $C^k$ functions ($\pmb{F}_1: \mathbb{R}^3\to\mathbb{R}^3$) to $C^{k-1}$ functions ($\pmb{F}_2: \mathbb{R}^3\to\mathbb{R}^3$), denoted $\nabla\times\pmb{F}$ or $\mathrm{curl}\,\pmb{F}$. It describes the infinitesimal circulation (local “spinning” or “twisting” motion) of a vector field around a particular point in three-dimensional Euclidean space.

A nonzero curl tells us whether the vector field (such as flow) is rotating around a point, and if so,in which direction (clockwise or counterclockwise). In contrast, if the curl is zero, the field has no local rotation at that point.

The “curl” of a vector field $\pmb{F}$ at point $p$ is interpreted as the circulation density at that point of the field, that is,

$$\left(\nabla\times\pmb{F}\right)(p)\cdot\pmb{n}\triangleq\lim_{A\to 0}\frac{1}{|A|}\oint_C\pmb{F}\cdot\mathrm{d}\pmb{r}, \tag{8} \label{eq8}$$

where $A$ is a small area with $n$ as its normal vector, and the orientation of the closed curve $C$ bounding $A$ should follow the right-hand rule

with respect to $n$. $|A|$ is the area magnitude. $\oint_C\pmb{F}\cdot\mathrm{d}\pmb{r}$ represents the circulation of $\pmb{F}$ along the boundary $C$ enclosing point $p$.

Representation in Cartesian Coordinates #

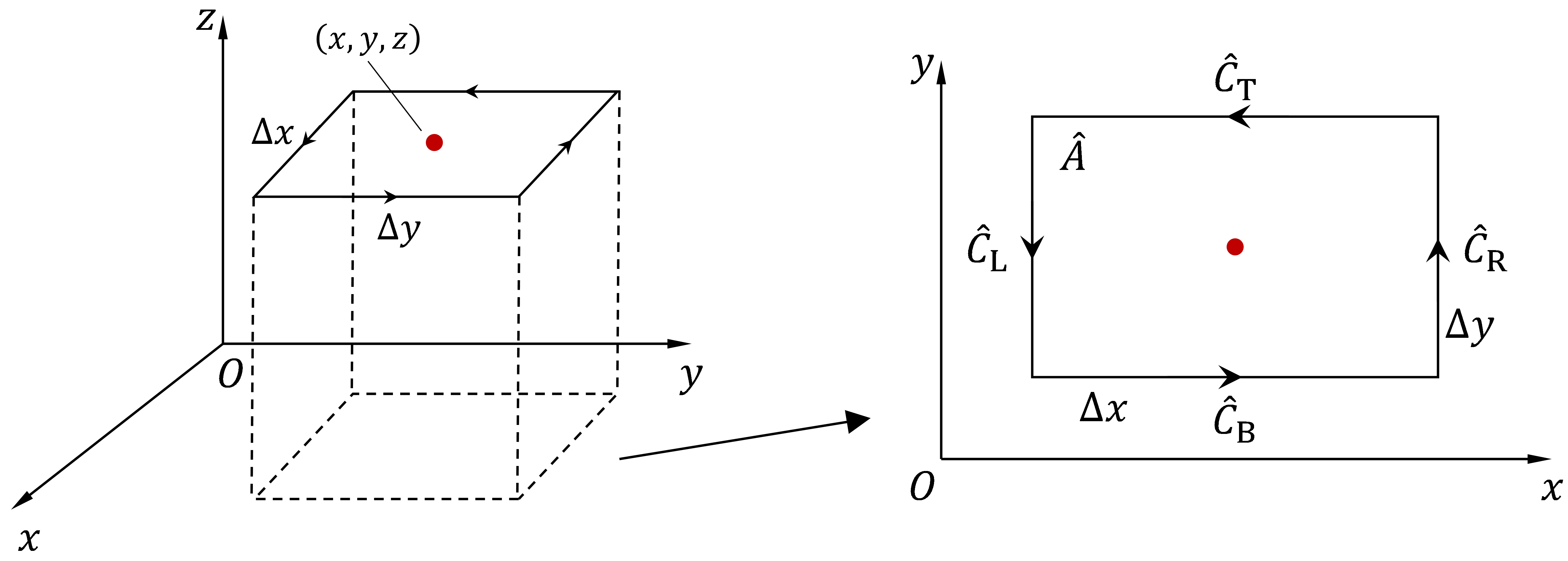

From equation $\eqref{eq8}$, we can find that by setting the normal vector $\pmb{n}$ to be $\pmb{i},\pmb{j},\pmb{k}$ in turn—the three orthonormal basis vectors corresponding to the Cartesian coordinate axes—we obtain the expression for $\mathrm{curl}\,\pmb{F}$ in Cartesian coordinates. Therefore, we calculate the $\pmb{k}$-component of the curl by taking $\pmb{n}=\pmb{k}$ as an example (the schematic diagram is provided in Fig. 2).

Figure 2: An infinitesimal rectangle with dimensions Δx and Δy, parallel to the xOy-plane, has its center at (x,y,z). The closed path is composed of four line segments parallel to the coordinate axes, oriented as shown by the arrows in the figure. The 'hat' symbol is used here to distinguish the projection path from the real integration path.

Here, a rectangular path parallel to the $xOy$-plane with dimensions $\Delta x$ and $\Delta y$ is chosen to calculate the line integral $\oint_\hat{C}\pmb{F}\cdot\pmb{t}\,\mathrm{d}r$. As $\hat{A}\to 0$, the line integral for each segment can be approximated by the value of $\pmb{F}\cdot\pmb{t}$ at the center of the segment, multiplied by its length. So we have

\begin{align} \int_{\hat{C}_\mathrm{B}}\pmb{F}\cdot\pmb{t}\,\mathrm{d}r&=\int_{\hat{C}_\mathrm{B}}F_x\,\mathrm{d}x\approx F_x\left(x,y-\frac{\Delta y}{2},z\right)\Delta x; \tag{9} \label{eq9}\\ \int_{\hat{C}_\mathrm{T}}\pmb{F}\cdot\pmb{t}\,\mathrm{d}r&=\int_{\hat{C}_\mathrm{T}}F_x\,\mathrm{d}x\approx -F_x\left(x,y+\frac{\Delta y}{2},z\right)\Delta x, \tag{10} \label{eq10} \end{align}

then we add equations $\eqref{eq9}$ and $\eqref{eq10}$, which gives the line integral on segment $\hat{C}_\mathrm{T}+\hat{C}_\mathrm{B}$. Similarly, that on segment $\hat{C}_\mathrm{L}+\hat{C}_\mathrm{R}$ can also be obtained. That is,

\begin{align} \frac{1}{|\hat{A}|}\int_{\hat{C}_\mathrm{T}+\hat{C}_\mathrm{B}}\pmb{F}\cdot\pmb{t}\,\mathrm{d}r&\approx -\frac{F_x\left(x,y+\frac{\Delta y}{2},z\right)-F_x\left(x,y-\frac{\Delta y}{2},z\right)}{\Delta y}; \tag{11} \label{eq11}\\ \frac{1}{|\hat{A}|}\int_{\hat{C}_\mathrm{L}+\hat{C}_\mathrm{R}}\pmb{F}\cdot\pmb{t}\,\mathrm{d}r&\approx -\frac{F_x\left(x+\frac{\Delta x}{2},y,z\right)-F_x\left(x-\frac{\Delta x}{2},y,z\right)}{\Delta x}. \tag{12} \label{eq12} \end{align}

Taking limit $\hat{A}\to 0$ and incorporating equations $\eqref{eq11}$ and $\eqref{eq12}$ finally gives the $\pmb{k}$ component of $\mathrm{curl}\,\pmb{F}$

$$\left(\nabla\times\pmb{F}\right)_z=\lim_{\hat{A}\to 0}\frac{1}{|\hat{A}|}\oint_\hat{C}\pmb{F}\cdot\pmb{t}\,\mathrm{d}r=\frac{\partial F_y}{\partial x}-\frac{\partial F_x}{\partial y}. \tag{13} \label{eq13}$$

We can also obtain components of the curl with respect to the other two basis vectors. Ultimately, the curl in Cartesian coordinates can be expressed as

$$\nabla\times\pmb{F}\triangleq\mathrm{curl}\,\pmb{F}=\left|\begin{array}{c} \pmb{i} & \pmb{j} & \pmb{k}\\ \partial/\partial x & \partial/\partial y & \partial/\partial z\\ F_x & F_y & F_z\\ \end{array}\right|. \tag{14} \label{eq14}$$

However, there is a question regarding the above process: if the chosen path is an arbitrary planar curve that is not parallel to the $xOy$-plane, will our conclusion still hold?

The answer is yes. First, we can prove that the conclusion holds for a right-angled triangular path. Any closed curve on the $xOy$-plane can be approximated by a polygon, and the area enclosed by the polygon can be fully divided using rectangles and right-angled triangles. Therefore, the line integral (circulation) around a polygon, in the limit as the number of small regions $N\to\infty$, will converge to the line integral around the closed curve $\hat{C}$. Finally, when the area enclosed by $\hat{C}$ shrinks to zero, the result gives the $z$-component of the curl, which can be shown to be consistent with equation $\eqref{eq13}$.

Furthermore, although we always assume that the region enclosed by the integration path is a plane, this is not a necessity. Since the definition of curl requires that the closed curve around a point shrinks to that point, in the limit, the surface will eventually approach the plane. Therefore, the conclusion previously stated still holds.

Green’s Theorem and Stokes’ Theorem #

Two important theorems are associated with the concept of “curl”. Green’s Theorem relates a line integral round a closed curve $C$ to an area integral over the plane region $A$ enclosed by $C$. The general form is given by

$$\oint_C\pmb{F}\cdot\,\mathrm{d}\pmb{r}=\iint_A\left(\nabla\times\pmb{F}\right)\cdot\,\mathrm{d}\pmb{A}. \tag{15} \label{eq15}$$

In Cartesian coordinate systems, we have $\pmb{F}=F_x\,\pmb{i}+F_y\,\pmb{j}$ and $\mathrm{d}\pmb{r}=\mathrm{d}x\,\pmb{i}+\mathrm{d}y\,\pmb{j}$. Hence, equation $\eqref{eq15}$ take the form

$$\oint_CF_x\,\mathrm{d}x+F_y\,\mathrm{d}y=\iint_A\left(\frac{\partial F_y}{\partial x}-\frac{\partial F_x}{\partial y}\right)\,\mathrm{d}x\mathrm{d}y. \tag{16} \label{eq16}$$

Stokes’ Theorem relates a line integral round a closed curve $C$ to a surface integral over the surface $S$ enclosed by $C$. Let $S$ be a smooth oriented surface in $\mathbb{R}^3$ bouned by a closed curve $C$. If the vector-valued function $\pmb{F}$ is first-order differentiable on a neighborhood of $S$, this theorem can be expressed as follows

$$\oint_C\pmb{F}\cdot\,\mathrm{d}\pmb{r}=\iint_S\left(\nabla\times\pmb{F}\right)\cdot\,\mathrm{d}\pmb{S}. \tag{17} \label{eq17}$$

In Cartesian coordinate systems, we have $\pmb{F}=F_x\,\pmb{i}+F_y\,\pmb{j}+F_z\,\pmb{k}$ and $\mathrm{d}\pmb{r}=\mathrm{d}x\,\pmb{i}+\mathrm{d}y\,\pmb{j}+\mathrm{d}z\,\pmb{k}$. Hence, equation $\eqref{eq17}$ can be expressed more explicitly as

\begin{align} \oint_CF_x\,\mathrm{d}x+F_y\,\mathrm{d}y+F_z\,\mathrm{d}z=&\iint_S\left(\frac{\partial F_z}{\partial y}-\frac{\partial F_y}{\partial z}\right)\,\mathrm{d}y\mathrm{d}z+\\ &\left(\frac{\partial F_x}{\partial z}-\frac{\partial F_z}{\partial x}\right)\,\mathrm{d}x\mathrm{d}z+\left(\frac{\partial F_y}{\partial x}-\frac{\partial F_x}{\partial y}\right)\,\mathrm{d}x\mathrm{d}y. \tag{18} \label{eq18} \end{align}

Note that, Green’s Theorem applies to the conversion between a plane and its boundary. It is the two-dimensional special case of Stokes’ Theorem (surface in $\mathrm{R}^3$). More generally, Green’s Theorem is equivalent to the Newton–Lebniz formula in one dimensional case and Gauss’s Theorem in three dimensional case. Therefore, a higher-dimensional (general) expression of these theorems can be concluded here

$$\int_\Omega\nabla\cdot\pmb{F}(\pmb{r})\,\mathrm{d}\pmb{r}=\int_{\Gamma}\pmb{F}(\pmb{r})\cdot\pmb{n}\,\mathrm{d}\Gamma, \tag{19} \label{eq19}$$

where $\Omega$ represents a generalized region, which could be a line, an area, or a volume. $\Gamma=\partial\Omega$ denotes the generalized boundary of that region, which could correspond to vertices, a closed curve, or a closed surface. The specific values of the variables in equation $\eqref{eq19}$ for different dimensions, along with the corresponding theorems, are shown in the Table below.

| Dimension | $\Omega$ |

$\Gamma$ |

$\nabla$ |

$\pmb{F}$ |

$\pmb{n}\,\mathrm{d}\Gamma$ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1D (Newton–Lebniz) | $[a,b]$ |

$x=a,b$ |

$\frac{\mathrm{d}}{\mathrm{d}x}$ |

$F(x)$ |

$\begin{align}1,&\ x=b;\\-1,&\ x=a\end{align}$ |

2D (Green’s $\eqref{eq16}$) |

$A$ |

$C$ |

$\left(\frac{\partial}{\partial x},\frac{\partial}{\partial y}\right)$ |

$\left(F_y,-F_x\right)$ |

$(dy,-dx)$ |

3D (Gauss’s $\eqref{eq7}$) |

$V$ |

$S$ |

$\left(\frac{\partial}{\partial x},\frac{\partial}{\partial y},\frac{\partial}{\partial z}\right)$ |

$\left(F_x,F_y,F_z\right)$ |

$(\mathrm{d}y\mathrm{d}z,\mathrm{d}x\mathrm{d}z,\mathrm{d}x\mathrm{d}y)$ |

Below, we present a compilation of commonly used equations involving combinations of differential operators for further reference:

\begin{align} &\nabla\cdot\left(\nabla\times\pmb{F}\right)=0;\\ &\nabla\times\left(\nabla F\right)=\pmb{0};\\ &\nabla\cdot\left(\nabla F\right)\triangleq\nabla^2 F=\Delta F;\\ &\nabla\times\left(\nabla\times\pmb{F}\right)=\nabla\left(\nabla\cdot\pmb{F}\right)-\Delta\pmb{F}, \end{align}

here, the (bolded) $\pmb{F}$ represents a vector-valued function, and $F$ is a scalar-valued function. The differential operator $\Delta=\frac{\partial^2}{\partial x^2}+\frac{\partial^2}{\partial y^2}+\frac{\partial^2}{\partial z^2}$ is known as the Laplace operator

.

Last modified on 2026-01-04