Preface #

Configurations infilled with microstructures (architected materials) achieve an excellent balance between the desired property/response and the issue of lightweight. In 1978, Bensoussan et al.1 first introduced asymptotic expansion to study the macroscopic behavior of periodic structures whose microstructure period is small compared to the spatial extent of the whole structure. With asymptotic analysis, two length scales can be separated in the case of linear elasticity, and the effective micro-to-macro properties are mathematically derived for the micro unit cell, thus homogenizing microstructures to an equivalent solid.

However, such periodic structures are less preferred when one needs to accommodate advanced or tailored engineering use. Therefore, heterogeneity has always been a theme pursued by researchers and scientists both in design community and in practical application. In contrast to periodic structures, spatially varying ones are just able to provide such heterogeneity due to aperiodic or irregular arrangement of constituent cells, which is the main reason they are currently attracting so much attention and popularity.

Our focus here revolves around how can a spatially varying microstructure (SVM) be represented in a computer? We will try to answer this question in the following sections. The main idea for the generation of SVM is based on Zhu et al., JMPS, 2019 .

Generation of Periodic Structures #

As is indicated by the name, the key to generate a periodic structure lies in the description of a (micro) representative cell. So, we first talk about the generation of a unit cell.

Topology Description Function (TDF) #

A TDF refers to an implicit way to describe the configuration geometry. Positions occupied by (one) solid material are assigned with positive TDF values; while in regions occupied by air or the other kind of material, TDF gets negative.

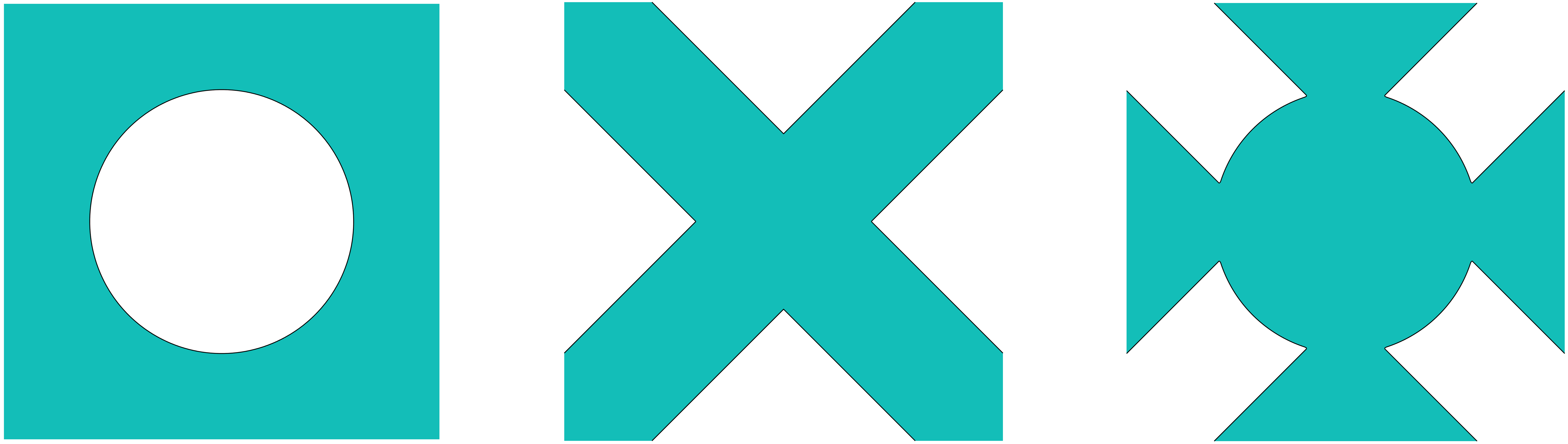

Figure 1: Plot of three different microscopic unit cells. The third cell is obtained by performing an intersection operation on the negation of the first two.

$$\phi(\pmb{x})\left\{\begin{aligned}&\geq 0,\quad \pmb{x}\in\mathrm{\Omega}^\mathrm{s};\\ &<0,\quad \pmb{x}\in\mathrm{\Omega}\backslash\mathrm{\Omega}^\mathrm{s},\end{aligned}\right. \tag{1} \label{eq1}$$

where the superscript “s” is used to denote the “solid” part of the configuration. Fig. 1 shows the plot of microscopic unit cells with three different geometries generated based on TDF.

The corresponding MATLAB code for generating the above cells is presented here.

% Define the plot definition and the corresponding step

M1 = 256; dx = 1/M1;

M2 = 256; dy = 1/M2;

% Representative cell of O-shape

R = 0.3; % circle radius

x0 = -1/2:dx:1/2;

y0 = -1/2:dy:1/2;

[X0,Y0] = meshgrid(x0,y0);

Z_O = X0.^2+Y0.^2 - R^2;

figure(1)

contourf(X0,Y0,Z_O,[0,0]);

axis equal;

axis off;

% Representative cell of X-shape

h = 0.2; % bar width

Z1 = h-abs(Y0-X0);

Z2 = h-abs(X0+Y0);

Z_X = max(Z1,Z2);

figure(2)

contourf(X0,Y0,Z_X,[0,0]);

axis equal;

axis off;

% Cell generated through Boolean operation

figure(3)

contourf(X0,Y0,max(-Z_O,-Z_X),[0,0]);

axis equal

axis off

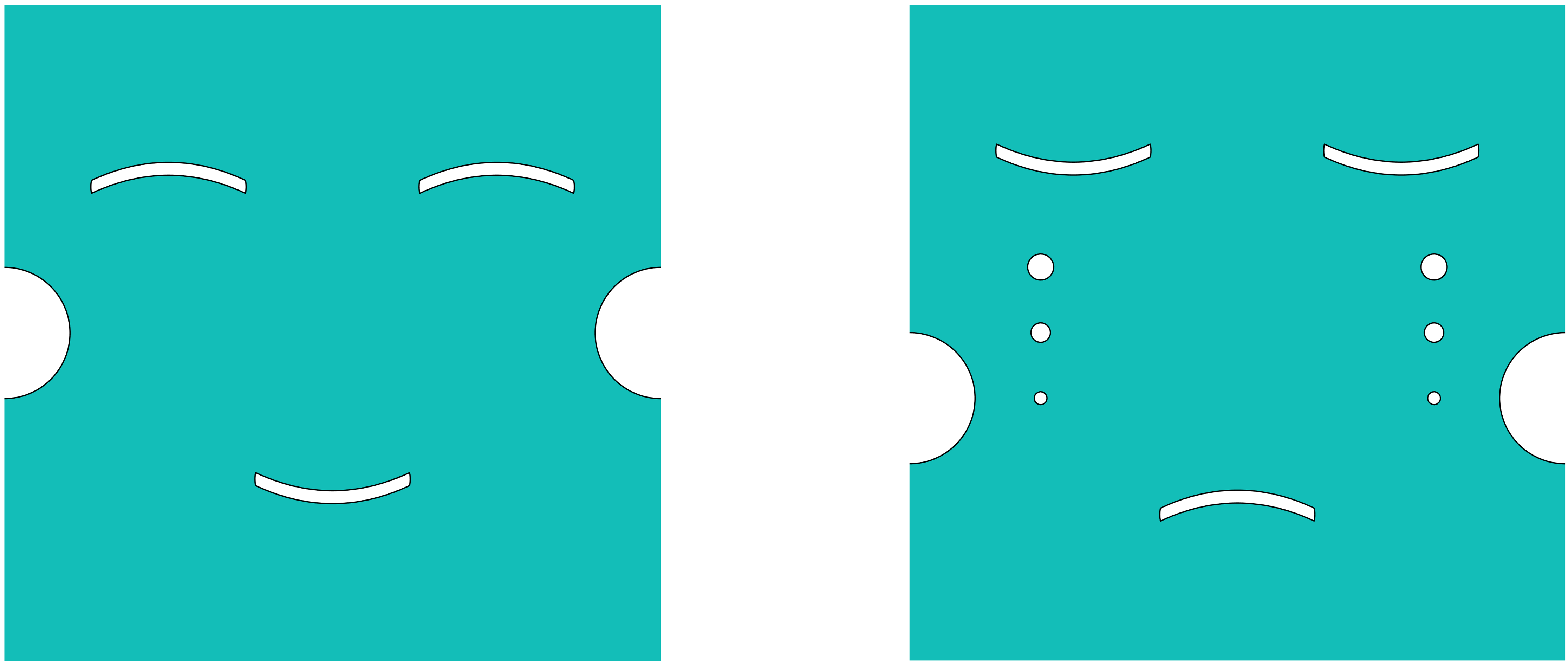

With TDF, we can go a step further to obtain more complex microstructural configurations, as demonstrated by the smiley and crying faces shown in the figure below (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: Cells with more complex geometries or topologies.

Note also that, the unit cell geometry can be described in a totally explicit manner with the aid of Non-Uniform Rational B-Spline (NURBS). In this context, both the inner and outer boundaries of unit cells have to be represented by NURBS curves or surfaces. So, the key to generating or storing representative cells is to capture control points that uniquely govern the NURBS. And one simply needs to drag these control points in order to change cell geometry/topology, which greatly enhances the design flexibility.

Periodic Arrangement #

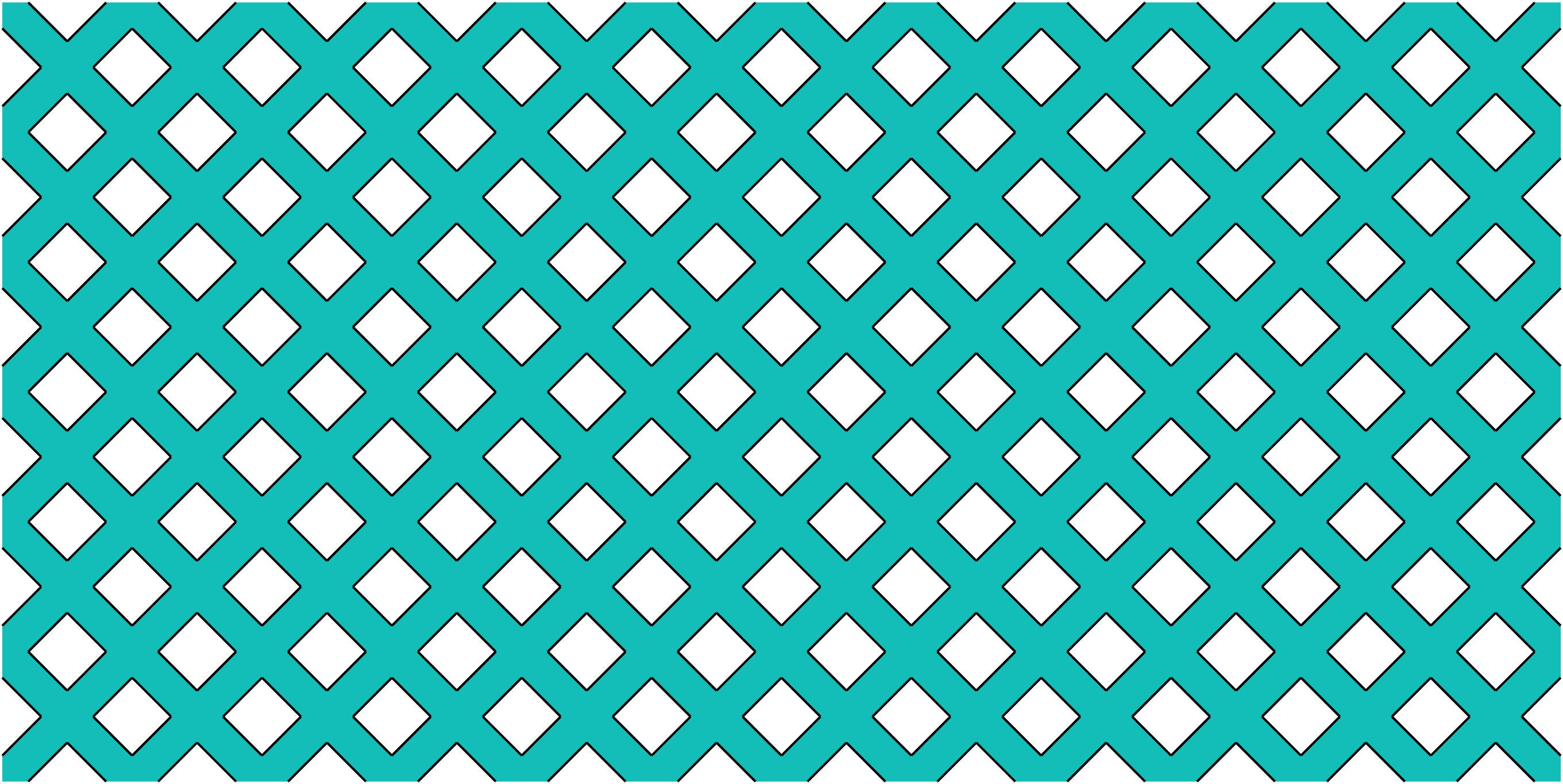

Periodic structure can then be obtained by periodically arranging the micro cells along two directions in the 2D space. The plot and code are presented below.

Figure 3: A periodic structure with the representative unit cell being X-shape.

N1 = 12; % number of cells along x-direction

N2 = 6; % ... along y-direction

M1 = 256; dx = 1/M1;

M2 = 256; dy = 1/M2;

%% Generation of the matrix cell

x0 = -1/2:dx:1/2;

y0 = -1/2:dy:1/2;

[X0,Y0] = meshgrid(x0,y0);

% Constituent cell (X-shape)

h = 0.2;

Z1 = h-abs(Y0-X0);

Z2 = h-abs(X0+Y0);

Z0 = max(Z1,Z2);

% Constituent cell (O-shape)

% R0 = 0.3;

% Z0 = X0.^2+Y0.^2 - R0^2;

%% Generation of the periodic structure

x = 0:dx:N1; y = 0:dy:N2;

[X,Y] = meshgrid(x,y);

Z = zeros(M2*N2+1,M1*N1+1);

% periodic arrangement of unit cell

for i = 1:N2

for j = 1:N1

Z((i-1)*M2+1:i*M2+1,(j-1)*M1+1:j*M1+1) = Z0;

end

end

contourf(X,Y,Z,[0,0])

axis equal

axis off

Generation of SVM #

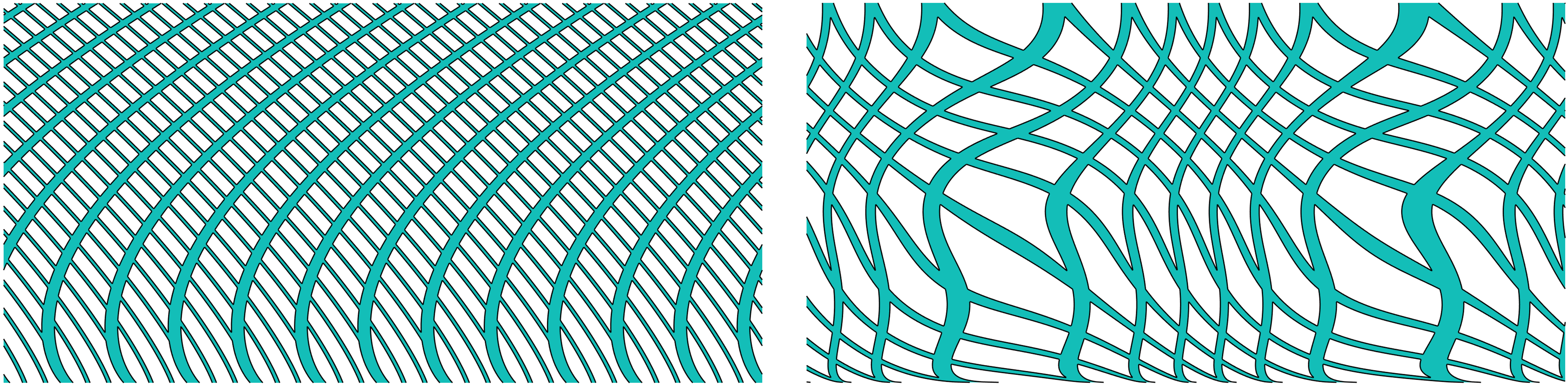

In order to generate the SVMs (as shown in Fig. 4), an intuitive idea is to start from periodic structures that can be easily obtained. Zhu et al. (2019) introduced a (continuous) macroscopic mapping function

Figure 4: Spatially varying microstructures with different mapping functions.

$\pmb{y}(\pmb{x})$ to connect multiscale structures in two spaces, the physical space ($\pmb{x}$) and the ficticious space ($\pmb{y}$). The former is occupied by the SVM while the latter is occupied by the spatially-periodic structure. And there is another space ($\bar{\pmb{\mathrm{Y}}}$) for investigating microscopic cells. This space is obtained by further scaling up the unit cell in the $\pmb{y}$-space to unit size, i.e., $\bar{\pmb{\mathrm{Y}}}=\frac{\pmb{y}}{h}$.

Following the idea of mapping operation, TDF for an SVM measured in $\pmb{x}$-coordinate is actually a composite function compared to that of a unit cell (Equation $\eqref{eq1}$).

$$\phi(\pmb{x})=\phi^\mathrm{p}\left(\frac{\pmb{y}(\pmb{x})}{h}\right),$$

here, the supuerscript “p” indicates that the TDF is associated with a periodic structure.

The main steps of the process include:

- Generation of the representative unit cell according to this section ;

- Compute the corresponding value of a specific grid point in the

$\pmb{y}$-coordinate based on the given mapping function$\pmb{y}(\pmb{x})$; - Getting the position of the particular (grid) element to which each point belongs in the periodic space based on the mapped coordinates;

- Interpolate the TDF value at the point based on the TDF values of the four nodes of the element (resembling shape functions in Finite Element Analysis);

- Traverse each grid point and follow steps 1-4 to obtain the TDF of an SVM.

Here we give the MATLAB code for the above process.

N1 = 6;

N2 = 3;

M1 = 256; dx = 1/M1;

M2 = 256; dy = 1/M2;

e = 1/2; % rescale paremeter (h)

%% Generation of the matrix cell

x0 = -1/2:dx:1/2;

y0 = -1/2:dy:1/2;

[X0,Y0] = meshgrid(x0,y0);

h = 0.1; % bar width

Z1 = h-abs(Y0-X0);

Z2 = h-abs(X0+Y0);

Z0 = max(Z1,Z2);

% R = 0.3; % circle radius

% Z0 = X0.^2+Y0.^2 - R^2;

%% Generation of the graded structure

Phi = zeros(M2*N2+1,M1*N1+1); % initialization of the TDF of an SVM

i = 1; j = 1; % counting variables

% calculate the value of y (y=y(x)) on each node measured in x-coordinate on a coarse grid

for m = 0:dx:N1

for n = 0:dy:N2

x = 2*m+n; % macroscopic mapping function

y = m+n^1.5;

% x = m+0.3*sin(2*m)+n^0.5;

% y = 0.8*n+0.2*sin(3*n);

a = floor(x/(dx*e)); % the column subscript of the bottom-left point of the element to which (m,n) belongs

b = floor(y/(dy*e)); % the row subscript of the bottom-left point of the element to which (m,n) belongs

a0 = mod(a,M1);

b0 = mod(b,M2);

L1 = (x-(a+1)*(dx*e))/(dx*e)*(y-(b+1)*(dy*e))/(dy*e);

L2 = -(x-a*(dx*e))/(dx*e)*(y-(b+1)*(dy*e))/(dy*e);

L3 = (x-a*(dx*e))/(dx*e)*(y-b*(dy*e))/(dy*e);

L4 = -(x-(a+1)*(dx*e))/(dx*e)*(y-b*(dy*e))/(dy*e);

Phi(j,i) = L1*Z0(M2+1-b0,a0+1)+L2*Z0(M2+1-b0,a0+2)+L3*Z0(M2-b0,a0+2)+L4*Z0(M2-b0,a0+1);

j = j+1;

end

i = i+1;

j = 1;

end

% get the mesh grid of the coordinates for generating an SVM

x1 = 0:dx:N1;

y1 = 0:dy:N2;

[X,Y] = meshgrid(x1,y1);

contourf(X,Y,Phi,[0,0])

axis equal

axis off

Closing #

This mapping-based framework can be easily extended to more complex situations, including decoration of microstructures on complex manifolds, generation of three-dimensional structures infilled with graded microstructures, the introduction of NURBS, and so on. Moreover, the graded-to-periodic mapping makes it possible to analyze these complex multiscale structures. Methodologically, only the mapping Jacobian needed to be included in the original asymptotic homogenization framework proposed for periodic/quasi-periodic structures.

One more thing needs to be mentioned for the last aspect, the generation of a NURBS surface (solid) is just a mapping process from unit square (unit cubic entity) to an arbitrary physical surface (solid). By analogy, such a NURBS expression can be used as the abovementioned mapping function $\pmb{y}=\pmb{y}(\pmb{x})$. And one can simply adopt the approach of explicit description in the context of NURBS representation. Therefore, everything w.r.t. the generated SVM is explicit and can be compressed to control points that govern cell geometry and the corresponding macroscopic mapping function.

Finally, we provide several relevant references for readers interested in further exploring this field, including topics such as the generation2, analysis3, and optimization4 of SVM.

-

Bensoussan A, Lions JL, Papanicolau G. Asymptotic Analysis for Periodic Structures. Elsevier; 1978. ↩︎

-

D. Xue, Y. Zhu, X. Guo, Generation of smoothly-varying infill configurations from a continuous menu of cell patterns and the asymptotic analysis of its mechanical behaviour , Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Engrg. 366 (2020) 113037. ↩︎

-

Li S, Zhu Y, Guo X. Optimisation of spatially varying orthotropic porous structures based on conformal mapping . Comput Methods Appl Mech Eng. 2022;391:114589. ↩︎

-

Chuang Ma, Jianhao Zhang, Yichao Zhu, Performance analysis and optimisation of spatially-varying infill microstructure within CAD geometries , Comput Methods Appl Mech Eng., 2023, 416:116373. ↩︎

Last modified on 2026-01-04