To Start With: Several core ingredients regarding score-based generative models — the Langevin equation, the (Stein’s) score function, and the score-matching loss.

Langevin Equation: From the Perspective of Sampling #

Suppose that if we are given $p(\pmb{x})$, we should aim to draw samples from a location where $p(\pmb{x})$ has a high value. Thus an optimization scheme can be naturally obtained from the idea of searching for a higher probability

$$\pmb{x}^\ast=\mathop{\arg\max}\limits_{\pmb{x}} log\,p(\pmb{x}),$$

and the goal is to maximize the log-likelihood of the distribution $p(\pmb{x})$. Before going deeper into Langevin equation, we first leave a comment about the difference between the maximization here and maximum likelihood estimation. In the former scheme, we have fixed model parameters and a changing data point; while in the latter one, the data point $\pmb{x}$ is fixed but the model parameters are changing. Intuitively, we have the following table to summarize the difference.

| Problem | Sampling | Maximum Likelihood |

|---|---|---|

| Optimization target | A sample point $\pmb{x}$ |

Model parameters $\pmb{\theta}$ |

| Formulation | $\pmb{x}^\ast=\mathop{\arg\max}\limits_{\pmb{x}} log\,p(\pmb{x}; \pmb{\theta})$ |

$\pmb{\theta}^\ast=\mathop{\arg\max}\limits_{\pmb{\theta}} log\,p(\pmb{x}; \pmb{\theta})$ |

Instead of being a simple parameteric model, which can be studied by analytic solutions, optimizations of $p(\pmb{x})$ in a high-dimensional space are generally ill-posed with many local minima. Therefore, there exists no single algorithm that is globally converging in all situations. A reasonable trade-off between computational complexity, memeory requirement, difficulty of implementation, and solution quality is the gradient descent algorithm, a first-order method. For optimization with the objective function being $log\,p(\pmb{x})$, we have an update rule defined by the gradient descent algorithm

$$\pmb{x}_{t+1}=\pmb{x}_t+\tau\nabla_{\pmb{x}}log\,p(\pmb{x}_t),$$

where $\tau$ is the step size which users can control.

We won’t go into detail about the mathematical derivation of Langevin dynamics here (refer to this blog for details), but will simply treat it as an iterative process that allows us to draw samples. Here, we present the corresponding definition.

The (discrete-time) Langevin equation for sampling from a known distribution

$p(\pmb{x})$is an iterative precodure for$t=1,\cdots,T$:$$\pmb{x}_{t+1}=\pmb{x}_t+\tau\nabla_{\pmb{x}}log\,p(\pmb{x}_t)+\sqrt{2\tau}\pmb{\epsilon},\quad \pmb{\epsilon}\sim\mathcal{N}\left(\pmb{\epsilon}; \pmb{0}, \pmb{\mathrm{I}}\right), \tag{1} \label{eq1}$$where$\pmb{x}_0$is the white noise, which is randomly sampled from a prior distribution (such as uniform).$\pmb{\epsilon}$is an extra noise term to ensure that the generated samples do not always collapse onto a mode, but hover around it for diversity.

Note that, in generative models, Langevin equation = gradient descent + noise is applied to the log-likelihood function. One question arises: why do we need an extra “noise” instead of just “gradient descent”?

Here is one interpretation: The problem we are interested in is sampling from a distribution instead of the optimization. With the introduction of a random noise to the original gradient descent step, we can randomly pick a sample that follows the trajectory of the objective function while not collapsing onto a deterministic mode. If we are closer to the peak, we will move left and right slightly; if we are far from the peak, the gradient direction will pull us towards the peak. In a word, by repeatedly initialize the algorithm at a uniformly distributed location, we will eventually collect samples that will follow the designated distribution.

Langevin Equation: From the Perspective of Energy-based Models

Starting from the energy-based model serves as another path to arrive at the score function. This blog

have shown that we can actually train a VDM by optimizing a neural network (NN) $\pmb{s}_{\pmb{\theta}}(\pmb{x}_t, t)$ to predict the score function $\nabla log\,p(\pmb{x}_t)$. The score term in that derivation arises directly from Tweedie’s Formula, which offers limited insight into the nature of the score function or the reasons for modeling it. Therefore, we resort to another class of generative models, Score-based Generative Models12, for some interpretations. And from the perspective of the results, the previously derived VDM can be shown to have an equivalent Score-based Generative Modeling formulation, which allows us to flexibly switch between these two interpretations.

Instead of directly starting from showcasing “why score function?”, we first revisit the energy-based models34. Arbitrarily flexible probability distributions can be expressed by:

$$p_{\pmb{\theta}}(\pmb{x})=\frac{1}{Z_{\pmb{\theta}}}e^{-f_{\pmb{\theta}}(\pmb{x})}, \tag{2} \label{eq2}$$

where $f_{\pmb{\theta}}(\pmb{x})$ denotes an arbitrary flexible, parameterizable function. It is called the energy function and often modeled by a NN. $Z_{\pmb{\theta}}$ is a normalizing constant to ensure $\int p_{\pmb{\theta}}(\pmb{x})\,\mathrm{d}\pmb{x}=1$. Maximum likelihood poses a possible way to learn such a distribution; however, this requires tractably computing the normalizing constant $Z_{\pmb{\theta}}=\int e^{-f_{\pmb{\theta}}(\pmb{x})}\,\mathrm{d}\pmb{x}$, which may not be accessible for complex $f_{\pmb{\theta}}(\pmb{x})$ functions.

Training a NN

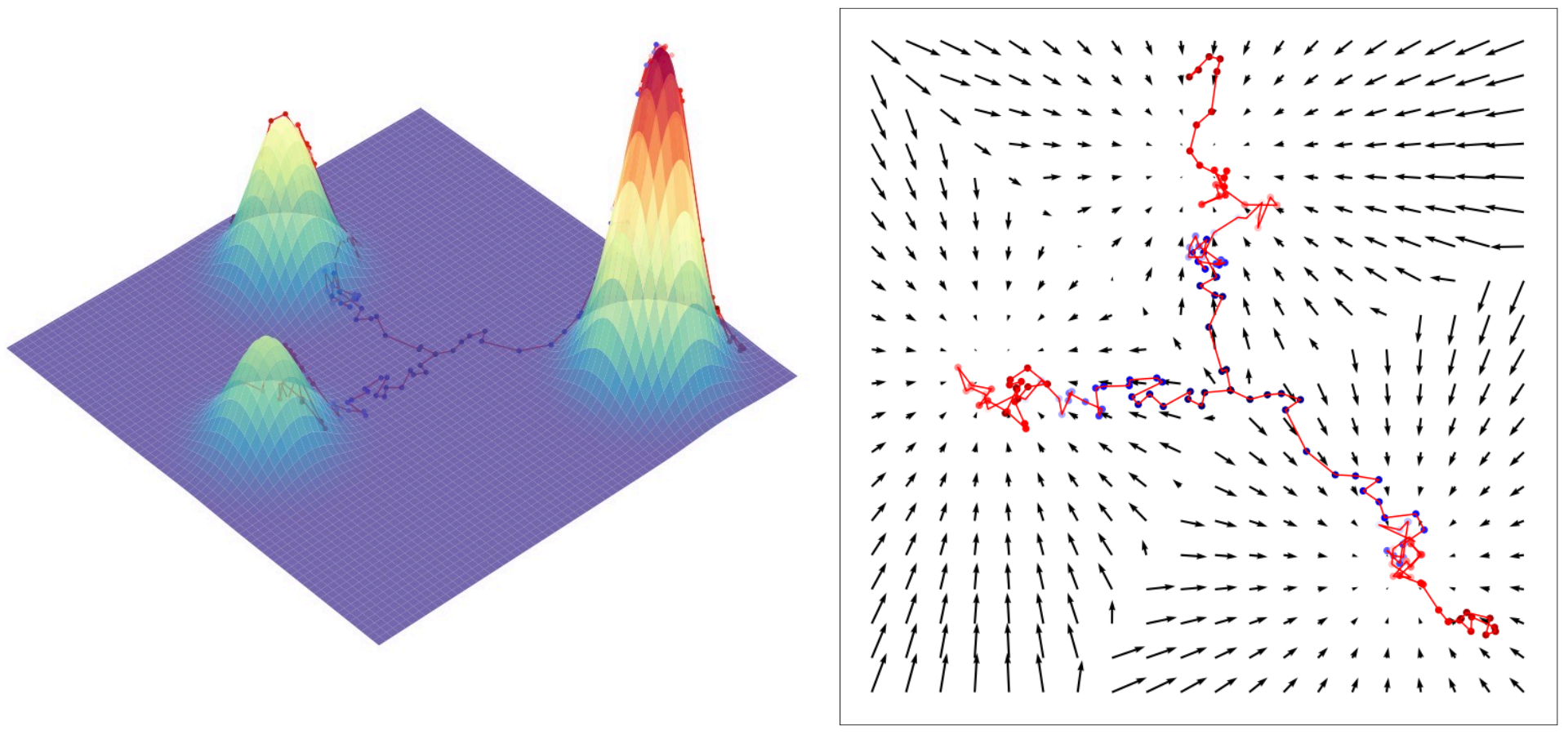

Figure 1: Visualization of three random sampling trajectories generated with Langevin dynamics, all starting from the same initialization point, for a Mixture of Gaussians. The left figure plots these sampling trajectories on a 3D contour, while the right figure plots sampling trajectories against the ground truth score function (Calvin Luo, 2022).

$\pmb{s}_{\pmb{\theta}}(\pmb{x})$ to learn the score function $\nabla log\,p(\pmb{x}_t)$ of distribution $p(\pmb{x})$ turns out to be a way out of calculating or modeling $Z_{\pmb{\theta}}$. To arrive at this conclusion, we simply take the derivative of the log of both sides of Equation $\eqref{eq2}$:

\begin{align} \nabla_{\pmb{x}} log\,p_{\pmb{\theta}}(\pmb{x}_t) &= \nabla_{\pmb{x}} log\left(\frac{1}{Z_{\pmb{\theta}}}e^{-f_{\pmb{\theta}}(\pmb{x})}\right) \tag{3}\\ &= \nabla_{\pmb{x}} log\frac{1}{Z_{\pmb{\theta}}}+\nabla_{\pmb{x}} log\,e^{-f_{\pmb{\theta}}(\pmb{x})} \tag{4}\\ &= -\nabla_{\pmb{x}} f_{\pmb{\theta}}(\pmb{x}) \tag{5}\\ &\approx \pmb{s}_{\pmb{\theta}}(\pmb{x}). \tag{6} \end{align}

Note that, this is represented as a NN without involving any normalization constants. The specific explanation for the above derivation is that, for every $\pmb{x}$, taking the gradient of its log likelihood w.r.t. $\pmb{x}$ points out the exact direction in data space to move in order to further increase the likelihood. As is illustrated in the left panel of Fig. 1.

The score function defines a vector field over the entire space, pointing towards the modes (as shown in the right panel of Fig. 1). So, by learning the score of the true data distribution, samples can be generated by starting at any arbitrary point in the same space and then iteratively following the direction to finally reach a mode. This sampling procedure is known as Langevin dynamics defined by Equation $\eqref{eq1}$.

Also, from the same initialization point, we can generate samples from different modes due to the stochastic noise term $\sqrt{2\tau}\pmb{\epsilon}$ in the Langevin equation; without it, sampling from a fixed point would always deterministically follow the score to the same mode at every trial. This is particularly useful when sampling is initialized from a position that lies between multiple modes.

(Stein’s) Score Function #

The second term on the right side of Langevin dynamics equation (Equation $\eqref{eq1}$) is known as the Stein’s score function, which is denoted by

$$\pmb{s}_{\pmb{\theta}}(\pmb{x})\overset{\mathrm{def}}{=}\nabla_{\pmb{x}}log\,p_{\pmb{\theta}}(\pmb{x}), \tag{7} \label{eq7}$$

notice that, the word “Stein’s” is added here to distinguish it from the ordinary score function, which takes the form

$$\pmb{s}_{\pmb{x}}(\pmb{\theta})\overset{\mathrm{def}}{=}\nabla_{\pmb{\theta}}log\,p_{\pmb{\theta}}(\pmb{x}).$$

Maximum likelihood estimation uses the ordinary score function, whereas Langevin dynamics uses Stein’s score function.

The key to understand the score function is to remember that it is the gradient w.r.t. the data $\pmb{x}$. So, for any high-dimensional distribution $p(\pmb{x})$, the gradient yields a vector field

$$\nabla_{\pmb{x}}log\,p_{\pmb{\theta}}(\pmb{x})=\left[\frac{\partial log\,p(\pmb{x})}{\partial x}, \frac{\partial log\,p(\pmb{x})}{\partial y}\right]^\mathrm{T}.$$

Geometric Interpretations of the Score Function #

Take Fig. 1 as an illustration.

- The magnitude of vectors corresponds to that of

$\nabla_{\pmb{x}}log\,p(\pmb{x})$. So, when$log\,p(\pmb{x})$approaches the peak, the gradient will be very weak. - The vector field indicates how a data point should travel in the contour map. Specifically, a data point will be dragged all the way towards the basin (where we have the weakest gradient) by the Langevin dynamics.

- Physically, the score function is equivalent to the “drift”. This suggests how the diffusion particles should flow to the lowest energy state.

Score Matching Techniques #

We should realize that we generally have no access to the ground truth $p(\pmb{x})$ in the Langevin equation. Fortunately, there are several cheap and dirty ways to approximate the ground truth score function.

Explicit Score Matching (ESM). Given a dataset $\chi=\left\lbrace\pmb{x}^{(1)},\cdots,\pmb{x}^{(M)}\right\rbrace$, the solution one may came up with is to consider the classical kernal density estimation by defining a distribution

$$q_h(\pmb{x})=\frac{1}{M}\sum_{m=1}^M\frac{1}{h}K\left(\frac{\pmb{x}-\pmb{x}^{(m)}}{h}\right), \tag{8} \label{eq8}$$

where $h$ is a certain hyperparameter for the kernal function $K( \cdot )$, and $\pmb{x}^{(m)}$ represents the $m$-th sample in the training set.

Equation $\eqref{eq8}$ indicates that the sum of all individual kernals yields the overall kernal density estimate $q(\pmb{x})$. Therefore, $q(\pmb{x})$ is at best an approximation to the unknown true data distribution $p(\pmb{x})$. And we can learn $\pmb{s}_{\pmb{\theta}}$ based on $q(\pmb{x})$ as a compromise. This leads to the following definition of the loss function which can be used to train a NN.

The explicit score matching loss is

\begin{align} J_{\mathrm{ESM}}(\pmb{\theta})&\overset{\mathrm{def}}{=}\frac{1}{2}\mathbb{E}_{p(\pmb{x})}\left[\|\pmb{s}_{\pmb{\theta}}(\pmb{x})-\nabla_{\pmb{x}}log\,p(\pmb{x})\|^2\right]\\ &\approx\frac{1}{2}\mathbb{E}_{q_h(\pmb{x})}\left[\|\pmb{s}_{\pmb{\theta}}(\pmb{x})-\nabla_{\pmb{x}}log\,q_h(\pmb{x})\|^2\right]. \tag{9} \label{eq9} \end{align}

Substituting Equation $\eqref{eq8}$ into Equation $\eqref{eq9}$, the loss is finally derived by

\begin{align} J_{\mathrm{ESM}}(\pmb{\theta})&\overset{\mathrm{def}}{=}\mathbb{E}_{p(\pmb{x})}\left[\|\pmb{s}_{\pmb{\theta}}(\pmb{x})-\nabla_{\pmb{x}}log\,p(\pmb{x})\|^2\right]\\ &\approx \int\|\pmb{s}_{\pmb{\theta}}(\pmb{x})-\nabla_{\pmb{x}}log\,q_h(\pmb{x})\|^2q_h(\pmb{x})\,\mathrm{d}\pmb{x}\\ &= \frac{1}{M}\sum_{m=1}^M\int\frac{1}{h}\|\pmb{s}_{\pmb{\theta}}(\pmb{x})-\nabla_{\pmb{x}}log\,q_h(\pmb{x})\|^2K\left(\frac{\pmb{x}-\pmb{x}^{(m)}}{h}\right)\,\mathrm{d}\pmb{x}. \end{align}

The derived loss can be used to train the network $\pmb{s}_{\pmb{\theta}}$. Once trained, we can replace the score term in the Langevin equation to obtain the recursion:

$$\pmb{x}_{t+1}=\pmb{x}_t+\tau\pmb{s}_{\pmb{\theta}}(\pmb{x}_t)+\sqrt{2\tau}\pmb{\epsilon}.$$

- Drawback regarding this approximation is that the kernal density estimation

$q(\pmb{x})$is a fairly poor non-parameter estimation of the ground truth$p(\pmb{x})$. In particular, if the number of samples is limited and the samples live in a high dimensional space, this approximation performance turns out to be poor.

Implicit Score Matching (ISM). In this method, the original ESM loss (Equation $\eqref{eq9}$) is changed to an implicit one

$$J_{\mathrm{ISM}}(\pmb{\theta})\overset{\mathrm{def}}{=}\mathbb{E}_{p(\pmb{x})}\left[\mathrm{Tr}(\nabla_{\pmb{x}}\pmb{s}_{\pmb{\theta}}(\pmb{x}))+\frac{1}{2}\|\pmb{s}_{\pmb{\theta}}(\pmb{x}))\|^2\right], \tag{10} \label{eq10}$$

here $\nabla_{\pmb{x}}\pmb{s}_{\pmb{\theta}}(\pmb{x}))$ is the Jacobian of $\pmb{s}_{\pmb{\theta}}(\pmb{x}))$. The ISM loss (Equation $\eqref{eq10}$) can be approximated by Monte Carlo

$$J_{\mathrm{ISM}}(\pmb{\theta})\approx\frac{1}{M}\sum_{m=1}^M\sum_{i}\left(\partial_i\pmb{s}_{\pmb{\theta}}(\pmb{x}^{(m)})+\frac{1}{2}\left|\left[\pmb{s}_{\pmb{\theta}}(\pmb{x}^{(m)})\right]_i\right|^2\right),$$

where $\partial_i\pmb{s}_{\pmb{\theta}}(\pmb{x}^{(m)})=\frac{\partial}{\partial x_i}\left[\pmb{s}_{\pmb{\theta}}(\pmb{x})\right]_i=\frac{\partial^2}{\partial x_i^2}log\,p(\pmb{x})$. If a deep NN is used to model the score function, the computation of trace operator can be overwhelming. Therefore, the ISM is not scalable.

Denoising Score Matching (DSM). In view of the potential limits of ESM and ISM, the denoising score matching is introduced as a more popular matching technique, whose loss function is given by

$$J_{\mathrm{DSM}}(\pmb{\theta})\overset{\mathrm{def}}{=}\mathbb{E}_{q(\pmb{x},\pmb{x}^\prime)}\left[\frac{1}{2}\left\|\pmb{s}_{\pmb{\theta}}(\pmb{x})-\nabla_{\pmb{x}}log\,q(\pmb{x}|\pmb{x}^\prime)\right\|^2\right]. \tag{11} \label{eq11}$$

The key difference is that a conditional distribution $q(\pmb{x}|\pmb{x}^\prime)$ is introduced to take the place of $q(\pmb{x})$. With such a treatment, we do not require approximation, e.g., the kernal density estimation, for the distribution.

Here we give an example.

Consider a special case where $q(\pmb{x}|\pmb{x}^\prime)=\mathcal{N}\left(\pmb{x}; \pmb{x}^\prime, \sigma^2\right)$, we can let $\pmb{x}=\pmb{x}^\prime+\sigma\pmb{\epsilon}$. So, the modified score function take the following form

\begin{align} \nabla_{\pmb{x}}log\,q(\pmb{x}|\pmb{x}^\prime) &= \nabla_{\pmb{x}}log\frac{1}{\left(\sqrt{2\pi}\sigma\right)^d}\mathrm{exp}\left\{-\frac{\|\pmb{x}-\pmb{x}^\prime\|^2}{2\sigma^2}\right\}\\ &= \nabla_{\pmb{x}}\left\{-\frac{\|\pmb{x}-\pmb{x}^\prime\|^2}{2\sigma^2}-log\left(\sqrt{2\pi}\sigma\right)^d\right\}\\ &= -\frac{\pmb{x}-\pmb{x}^\prime}{\sigma^2} = -\frac{\pmb{\epsilon}}{\sigma}. \end{align}

Accordingly, the DSM loss function (Equation $\eqref{eq11}$) becomes

$$J_{\mathrm{DSM}}(\pmb{\theta})=\mathbb{E}_{q(\pmb{x}^\prime)}\left[\frac{1}{2}\left\|\pmb{s}_{\pmb{\theta}}(\pmb{x}^\prime+\sigma\pmb{\epsilon})+\frac{\pmb{\epsilon}}{\sigma}\right\|^2\right].$$

Change the dummy variable $\pmb{x}^\prime$ to $\pmb{x}$. Also, we find that sampling from $q(\pmb{x})$ can be replaced by sampling from $p(\pmb{x})$ when given a training dataset. Thus,

The DSM loss function is defined as

$$J_{\mathrm{DSM}}(\pmb{\theta})=\mathbb{E}_{p(\pmb{x})}\left[\frac{1}{2}\left\|\pmb{s}_{\pmb{\theta}}(\pmb{x}+\sigma\pmb{\epsilon})+\frac{\pmb{\epsilon}}{\sigma}\right\|^2\right]. \tag{12} \label{eq12}$$

It is worth mentioning that Equation $\eqref{eq12}$ is highly interpretable: the term $\pmb{x}+\sigma\pmb{\epsilon}$ refers to adding noise $\sigma\pmb{\epsilon}$ to a clean image $\pmb{x}$. And the score function $\pmb{s}_{\pmb{\theta}}$ should take this noisy image and predict the noise $\frac{\pmb{\epsilon}}{\sigma}$. Predicting noise is equivalent to denoising, because any denoised image plus the predicted noise will yield the noisy observation. Therefore, we call Equation $\eqref{eq12}$ a denoising step.

Next we will show a theorem5 that establishes the equivalence between DSM and ESM. It is this equivalence that allows us to estimate the score function based on DSM.

For up to a constant

$C$which is independent of the variable$\pmb{\theta}$, it holds that$$J_{\mathrm{DSM}}(\pmb{\theta})=J_{\mathrm{ESM}}(\pmb{\theta})+C. \tag{13} \label{eq13}$$The detailed proof can be found in the paper Tutorial on Diffusion Models for Imaging and Vision (proof of theorem 3.4).

The training procedure of a score-based model is typically achieved by minimizing the DSM loss function. Given a training dataset $\left\{\pmb{x}^{(m)}\right\}_{m=1}^M$, the optimization goal is

\begin{align} \pmb{\theta}^\ast &= \mathop{\arg\max}\limits_{\pmb{\theta}}\mathbb{E}_{p(\pmb{x})}\left[\frac{1}{2}\left\|\pmb{s}_{\pmb{\theta}}(\pmb{x}+\sigma\pmb{\epsilon})+\frac{\pmb{\epsilon}}{\sigma}\right\|^2\right]\\ &\approx\mathop{\arg\max}\limits_{\pmb{\theta}}\frac{1}{2M}\sum_{m=1}^M\left\|\pmb{s}_{\pmb{\theta}}\left(\pmb{x}^{(m)}+\sigma\pmb{\epsilon}^{(m)}\right)+\frac{\pmb{\epsilon}^{(m)}}{\sigma}\right\|^2,\quad\pmb{\epsilon}^{(m)}\sim\mathcal{N}\left(\pmb{0},\mathrm{\pmb{I}}\right). \end{align}

Note that, the abovementioned training process assumes the noise level $\sigma$ to be fixed, however, it’s not difficult to ask for a generalization. The Noise Conditioned Score Network (NCSN) argued that one can instead optimize the following loss

$$J_{\mathrm{NCSN}}(\pmb{\theta})=\frac{1}{L}\sum_{i=1}^L\lambda(\sigma_i)\mathcal{l}(\pmb{\theta};\sigma_i),$$

where the individual loss function is defined according to the noise levels $\sigma_1,\cdot,\sigma_L$:

$$\mathcal{l}(\pmb{\theta};\sigma_i)=\mathbb{E}_{p(\pmb{x})}\left[\frac{1}{2}\left\|\pmb{s}_{\pmb{\theta}}(\pmb{x}+\sigma_i\pmb{\epsilon})+\frac{\pmb{\epsilon}}{\sigma_i}\right\|^2\right].$$

Based on empirical findings1, the coefficient function $\lambda(\sigma_i)$ is often chosen as $\lambda(\sigma_i)=\sigma_i^2$. And the noise level sequence often satisfies $\frac{\sigma_1}{\sigma_2}=\cdots=\frac{\sigma_{L-1}}{\sigma_L}>1$.

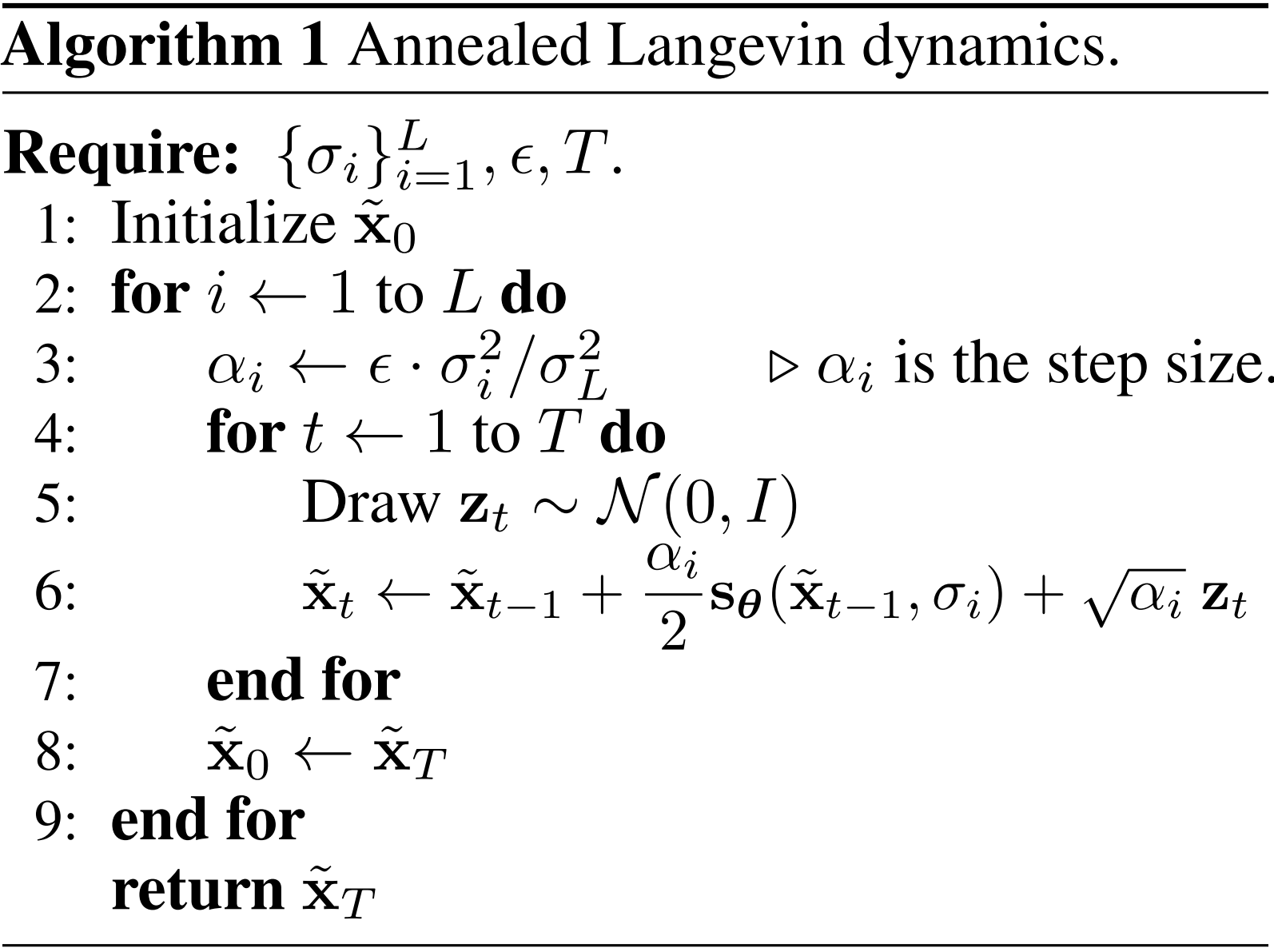

For inference, it is assumed that the score estimator $\pmb{s}_{\pmb{\theta}}$ has already been trained. Then, we can use the Langevin equation to iteratively draw samples by denoising the image. In NCSN, the corresponding Langevin equation can be implemented via an annealed importance sampling:

$$\pmb{x}_{t+1}=\pmb{x}_t+\frac{\alpha_i}{2}\pmb{s}_{\pmb{\theta}}(\pmb{x}_t,\sigma_i)+\sqrt{\alpha_i}\pmb{\epsilon}_t,\quad \pmb{\epsilon}_t\sim\mathcal{N}(\pmb{0},\pmb{\mathrm{I}}),$$

here $\alpha_i=\xi\cdot\sigma_i^2/\sigma_L^2$ is the step size and $\pmb{s}_{\pmb{\theta}}(\pmb{x}_t,\sigma_i)$ denotes the score estimator for noise level $\sigma_i$. Iteration over $t$ is repeated sequentially for each $\sigma_i,\ i=1,\cdots,L$.

Specific algorithm regarding the Annealed Langevin dynamics is shown in Fig. 2. The standard Gaussian

Figure 2: Algorithm on Annealed Langevin dynamics (Song and Ermon, 2019).

$\pmb{z}_t$ which serves as added noise is equivalent to the notation$\pmb{\epsilon}_t$ we used here, and $\epsilon$ is equivalent to $\xi$.

Closing #

Previous research on score matching reveals that when training a score function, we need a noise schedule so that score function can be trained better.

Other applications beyond generating images: restoration of important images such as deblurring, denoising, achieving super-resolution, etc.

-

Yang Song and Stefano Ermon. Generative modeling by estimating gradients of the data distribution . Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 32, 2019. ↩︎ ↩︎

-

Yang Song, Jascha Sohl-Dickstein, Diederik P Kingma, Abhishek Kumar, Stefano Ermon, and Ben Poole. Scorebased generative modeling through stochastic differential equations. arXiv preprint arXiv:2011.13456 , 2020. ↩︎

-

Yann LeCun, Sumit Chopra, Raia Hadsell, M Ranzato, and F Huang. A tutorial on energy-based learning. Predicting structured data, 1(0), 2006. ↩︎

-

Yang Song and Diederik P Kingma. How to train your energy-based models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2101.03288 , 2021. ↩︎

-

Pascal Vincent. A connection between score matching and denoising autoencoders . Neural Computation, 23(7):1661–1674, 2011. ↩︎

Last modified on 2026-01-04